Days, Dates and Calendars

There have been many changes to the calendar which affect the dating of documents in Scotland. During the middle ages the calendar did not conform to the solar year. Different countries solved the discrepancy by adopting the new ‘Gregorian’ calendar at different times. This leads to problems for the historian.

Medieval Calendar

The Julian calendar (introduced by Julius Caesar in 45 BC) was used throughout Europe until 1582. A standard year had 365 days, and every fourth year (a ‘leap year’) had an extra day, in order to match the calendar year to the solar year (i.e. the time taken for the earth to orbit the sun, calculated by classical astronomers as 365 ¼ days). This method of fixing the date was known as ‘Old Style’. In medieval Europe, including Scotland, the beginning of the year was usually 25 March (the feast of the Annunciation), so that the day after 24 March 1490 was 25 March 1491.

Gregorian Calendar

Medieval scholars noted that the year of 365¼ days was a slight overestimate, and by the 16th century this had caused a discrepancy of 10 days. Pope Gregory XIII corrected the error by cutting 10 days from the calendar in 1582 (so that 15 October 1582 followed 4 October 1582) and reformed the calendar to make the end year of every fourth century a leap year. The calendar became known as the ‘Gregorian Calendar’ after Pope Gregory, and dates calculated by the Gregorian Calendar are described as New Style. In addition, he decreed that the year should begin on 1 January. However, Pope Gregory’s reformation of the calendar was not accepted by most protestant states until the 18th century (and the 20th century in Russia, the Balkans and Greece). Scotland adopted the change to the start of the year in 1599 (31 December 1599 was followed by 1 January 1600). In the rest of the British Isles the change did not take place until 1 January 1752, under Chesterfield’s Act (24 Geo. II, c.23), which also removed the eleven days required to bring the British Isles (including Scotland) into New Style (2 September 1752 was followed by 14 September 1752). Some correspondents in the 17th and 18th centuries would actually mark two dates on a letter, e.g. ’17/29 March 1642′, to take account of the different calendars operating in different parts of Europe.

Problems for the historian

The historian may have problems correlating dates from different countries: e.g. a letter written in Scotland in February 1625 could be received in England in February 1624. In Scotland it is the custom among archivists and historians to use double dating for dates including the months of January – March prior to 1600, e.g. documents dated 10 March 1586 and 27 March 1587 should be written ’10 March 1586/87′ (or ’10 March 1586/1587’) and ’27 March 1587′, respectively.

The calendar in use in Scotland can be summarised as follows:

45BC – October 1582 AD Julian Calendar. Beginning of year was usually 25 March

October 1582 AD – 1599 AD Julian Calendar. Beginning of year was usually 25 March. (Some parts of Europe, but not Scotland, now used Gregorian calendar and 1 January as beginning of year).

1600AD – September 1752 AD Julian: but beginning of the year was 1 January. (25 March was still the beginning of the year in England and some other parts of Europe).

September 1752 AD – present Gregorian calendar. Beginning of the year is 1 January for all the British Isles.

Another problem facing historians of the later middle ages and early modern periods in Scotland, is that clerks sometimes employed a way of writing dates which look distinctly odd to the modern reader. This is the form of dating which, instead of using Arabic numerals (e.g. ’23rd June 1632′), used a corrupt Latin form (e.g. 23rd June JajvjC† and threttie twa yeiris). This kind of date, as illustrated in image 2, looks odd to us because they are a mixture of bad Latin and longhand numbers in Scots.

Contributors: Robin Urquhart, Alan Borthwick (both SCAN, 2002)

Bibliography

Cheney, C. R. (ed.) Handbook of Dates for Students of English History (Cambridge University Press, 1995)

David Ewing Duncan, The Calendar: the 5000-year struggle to align the clock and the heavens – and what happened to the missing ten days (Fourth Estate,1998)

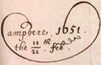

A double date from a document written in Campveere in the Netherlands and sent to Scotland on 21st February 1651 (according to the Gregorian Calendar operating at Campvere) but this was 11th February 1651 (according to the Julian calendar operating in Scotland at that time). From a document in the National Records of Scotland (reference: GD40/2/16).

An example of a Jaj date (‘Jajvijc† and eight yeares’): 1708

How can I find out what weekday a certain date fell on?

There are three main options: calendars on software packages, newspapers and directories or the Handbook of Dates.

Calendars on software packages

Some personal organiser packages for computers include calendar or diary functions which are back-dated by several centuries. However, these simply extend the current (Gregorian) calendar back to the earliest date in the package. This means that the calendar on your computer diverges from the calendar which operated in Scotland prior to 14 September 1752. For dates prior to 14 September 1752, you will need to consult Handbook of Dates for Students of English History ed. by C. R. Cheney (Cambridge University Press, 1995).

Newspapers and directories

If it is a date in the 19th or 20th centuries you should look at the back copy of a newspaper for that date. Many newspapers are now available through the British Newspaper Archive website (available free of charge in the National Library of Scotland or with a subscription elsewhere) https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

Alternatively, you could consult a Post Office Directory for the year in question. Post Office Directories include calendars for the year of publication, and these also include the dates of local holidays. Runs of Post Office Directories from the late 18th century to the 1970s are held by large reference libraries, such as Edinburgh City Libraries and the Mitchell Library, Glasgow.

Handbook of Dates

- Handbook of Dates for Students of English History ed. by C.R. Cheney (Cambridge University Press, 1995) is one of the most useful books for historians in Britain. Pages 83-160 allow you to work out a calendar for any year using fixed tables for all possible dates for Easter. Cheney’s tables will also allow the calculation of any date from 500AD onwards, but pay attention to discrepancies in the calendars of different parts of Europe between the 16th and 20th centuries.

How can I find out what national and local events happened on someone’s birthday?

National and local newspapers for the day in question (and the days following) should provide news reports on contemporary events. Some national newspapers can supply back issues, or facsimiles of front pages on a commercial basis. Many newspapers are now available through the British Newspaper Archive website (available free of charge in the National Library of Scotland or with a subscription elsewhere) https://www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk/

What were the Scottish quarter days?

Quarter days were the four days dividing the legal year, when rent and interest on loans were due, and when contracts and leases often began or ended.

In Scotland the quarter days were Candlemas (2 February); Whitsun (15 May); Lammas (1 August); and Martinmas (11 November).

The names recall saints’ days and festivals which pervaded medieval life. Candlemas was the feast of the Purification of the Virgin Mary, which was celebrated with the lighting of candles. Whitsunday is the seventh Sunday after Easter, but in Scotland the legal Whitsun was fixed on 15 May. Lammas was a harvest festival day, the name comes from the Old English hlafmaesse, meaning ‘loaf mass’. Martinmas was the feast of St Martin of Tours.

For a discussion of the use of saints’ days and festivals to date medieval documents see Handbook of Dates for Students of English History ed. by C.R. Cheney (Cambridge University Press, 1995). Some of the quarter days, and other feast days, were important occasions for markets, sports and popular entertainments. For more information about this see John Burnett, Riot, Revelry and Rout: sport in Scotland before 1860 (East Linton, 2000).

How can I decipher a date written in the form beginning ‘Jaj . . .’ in a 17th or 18th century document?

these are sometimes referred to by palaeographers as ‘Jaj dates’. The ‘Jaj’ part is a corruption of the Latin ‘i m’, meaning ‘1000’, the ‘vj’ is the Latin numeral for ‘6’, the ‘C†’ is an abbreviation of the Latin word ‘centum’ (‘one hundred’). Hence,

Jaj = 1000 vjC† = 600 and threttie twa yeiris = 32

= 1632

In image 3 the date 1663 is rendered: the year of God Jajvj C& saxti three

#gallery-3 { margin: auto; } #gallery-3 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-3 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-3 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */Jaj dates were still being written in the first decades of the eighteenth century, as image 4 shows: Jajvijc and eight yeares

#gallery-4 { margin: auto; } #gallery-4 .gallery-item { float: left; margin-top: 10px; text-align: center; width: 33%; } #gallery-4 img { border: 2px solid #cfcfcf; } #gallery-4 .gallery-caption { margin-left: 0; } /* see gallery_shortcode() in wp-includes/media.php */Note that, in this case, the C is not capitalised and does not have a mark of abbreviation for ‘centum’.

This form of dating is easy to learn by breaking it down into component parts:

The Jaj part (= 1000)

The v, or vj, or vij part (remember that the last i is usually a j)

The abbreviation for Centum and, which might appear as ‘C† and’ or ‘C†&’ or ‘C&’ or ‘C and’

The rest of the year written longhand, usually in Scots