Weights and Measures: Scottish Weight

In weight the basic unit was the Scots pound (from the Latin pondo, ‘by weight’, or pondus, meaning a ‘weight on a scale’), which equated roughly with the Roman weight, libra, hence the abbreviation of ‘lb.’. In Scots weight 16 pounds made a stone (from the word ‘stone’, i.e. a small piece of rock), although the avoirdupois stone was divided into 14 pounds. A sixteenth of a pound was an ounce (from the Latin uncia, meaning a ‘twelfth part’ – originally a pound was divided into 12 ounces). A sixteenth of an ounce was a drop or drap (possibly from a ‘drop’, i.e. a small amount of liquid, or from the Greek drachma, the origin of the Imperial equivalent, the dram).

Two main Scottish systems of weights were in use before 1707: the Scots troye weight (later known as the Dutch weight) and the Scots tron weight, introduced in the 15th century and maintained at 1¼ times the troy weight. The standards for these weights were adjusted four times. By 1824, according to Buchanan, two additional systems of weight were in use alongside these traditional weights: the English troy weight and the Avoirdupois weight. The juries empanelled under the 1824 Act found that there were significant local variations in the tron pound, which in Glasgow weighed 22½ ounces, in Dundee, 22 ounces, in Arbroath, Brechin and Montrose, 24 ounces and in Aberdeen, 28 ounces.[1]

Imperial weights were divided into troy and avoirdupois. Troy weight (the origin of the word troy is obscure but may come from the French town of Troyes) is used by silversmiths to measure gold, silver, gemstones, etc., and was used by apothecaries to measure small amounts of chemicals, etc. until 1864. Each pound was divided into 12 ounces. In avoirdupois weight (from the French meaning ‘to have weight’), which was used to measure bulkier goods, the pound had 16 ounces, which allowed for easier calculations into quarters.

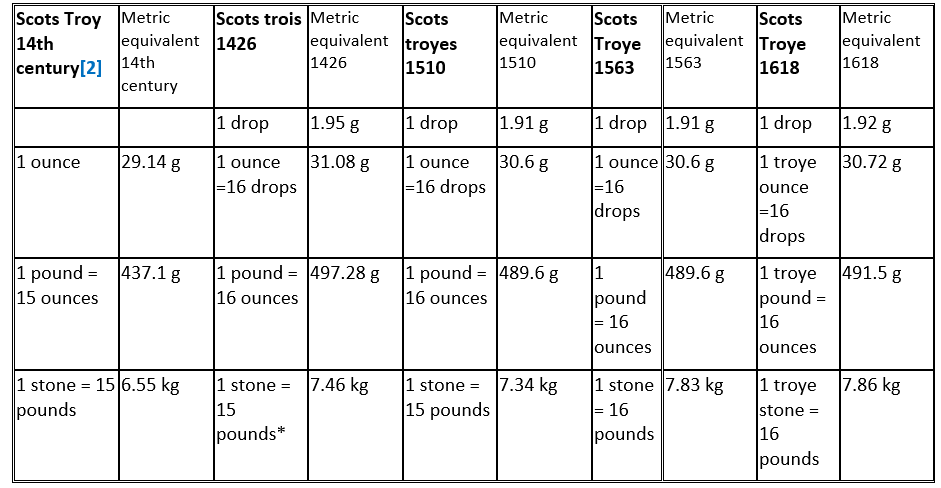

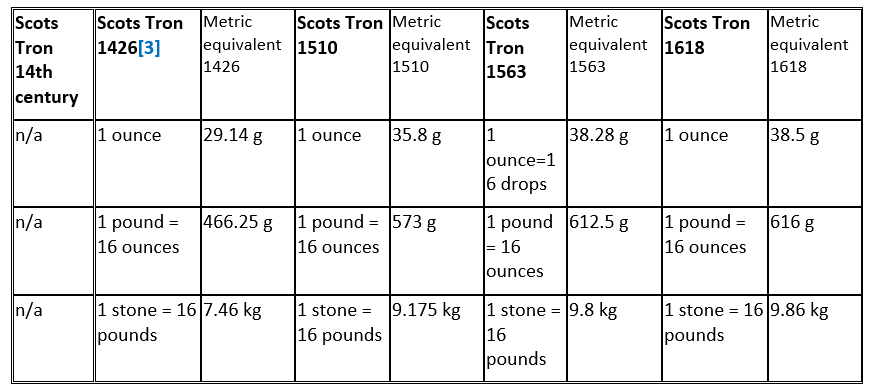

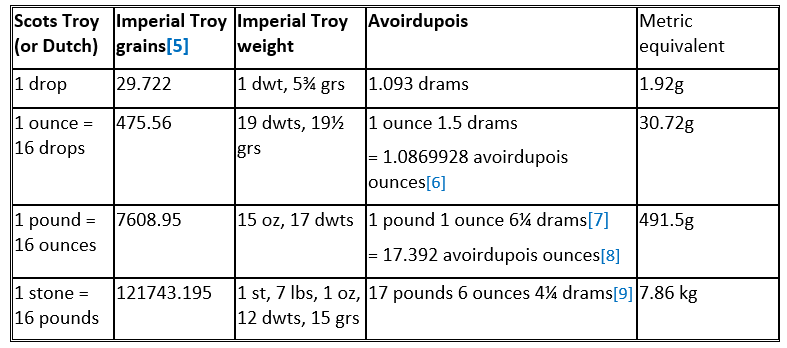

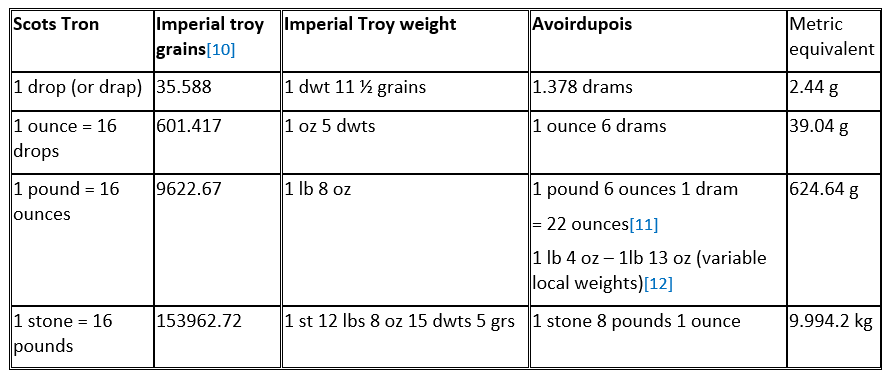

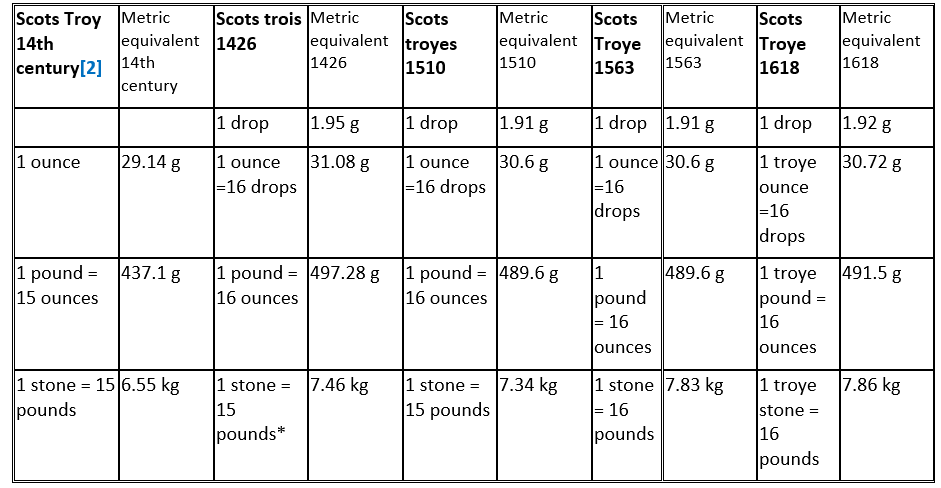

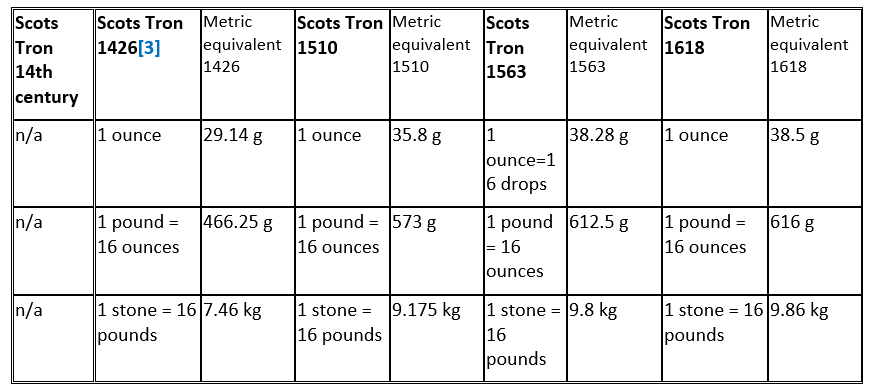

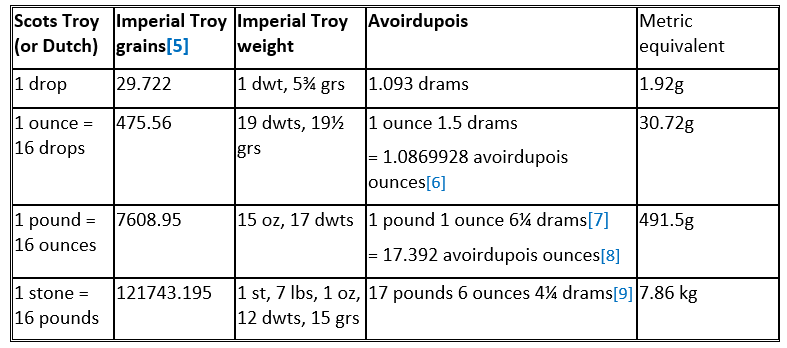

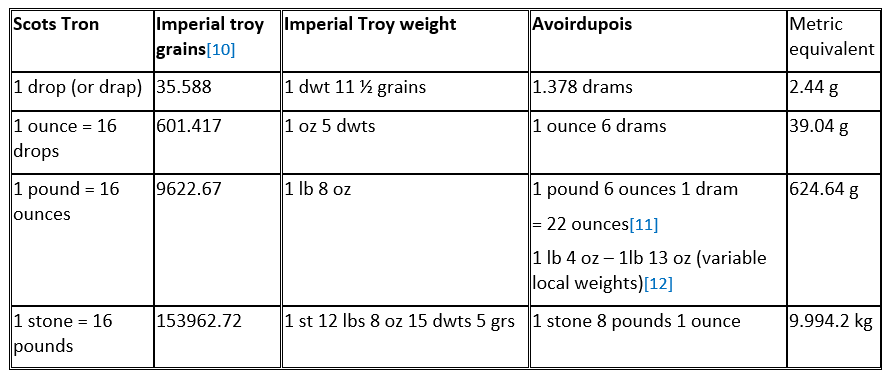

In all tables shown below the metric equivalent (rounded to two decimal points) is given as a guide only and should be regarded as approximate rather than definitive.

Troy Measure (or Dutch weight)

*Note that in 1426, 1 trois stone matched the weight of 1 tron stone.

Tron Measure

The weight standard for locally produced commodities, the stone, pound and ounce of which were each 1¼ times greater than the troy stone and pound.

Source: The above tables of weights are derived from R. D. Connor and A. D. C. Simpson, Weights and Measures in Scotland: A European Perspective, ed. by A. D. Morrison-Low (NMSE, 2004), pp. 749-53.

Determination after the Weights and Measures Act 1824

The Weights and Measures Act 1824 established the Imperial Troy pound as the base unit from which all other weights were derived. It also permitted the continued use of the Avoirdupois pound alongside the Troy pound. It did not define how many Troy pounds were in larger units but in practice the Avoirdupois amounts were used, resulting in 14 Troy pounds in a Troy stone and 8 Troy stones in a Troy hundredweight.

The relationships of the new Imperial system were as follows:

Imperial Standard Troy Pound (lb) = 5760 grains = 12 ounces (oz)

1 ounce = 480 grains = 20 Pennyweight (dwt)

1 Pennyweight = 24 grains (gr)

Avoirdupois hundredweight = 784000 grains = 4 quarters (8 stones)

Avoirdupois quarter = 196000 = 2 stones

Avoirdupois stone = 98000 = 14 pounds

Avoirdupois Pound = 7000 grains = 16 ounces

1 ounce = 437.5 grains = 16 drams

1 dram = 27.34375 grains

1 Avoirdupois lb = 1 lb 2oz 11 dwts 16 grs Imperial Troy[4]

1 Troy lb = 13 oz 2.651 drams Avoirdupois

Further information on Scots measurements can be found in the Dictionaries of the Scots Language <https://dsl.ac.uk/> [accessed 24 April 2024].

Compilers: SCAN contributors (2000). Editor: Elspeth Reid (2021)

Related Knowledge Base Entries

Weights and measures: origins of weights and measures in Scotland

Weights and Measures: Scottish Distance and Area

Weights and Measures: Scottish Dry Capacity

Weights and Measures: Scottish Liquid Capacity

Bibliography

Buchanan, George, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures Hitherto in Use in Great Britain…also Abstracts of the Jury Verdicts throughout Scotland in Regard to the Weights and Measures of Each County (Edinburgh 1829)

Connor, R. D., and A. D. C. Simpson, Weights and Measures in Scotland: A European Perspective, ed. by A. D. Morrison-Low (NMSE, 2004)

References

[1] George Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures Hitherto in Use in Great Britain […] also Abstracts of the Jury Verdicts throughout Scotland in Regard to the Weights and Measures of Each County (Edinburgh 1829), p. 24.

[2] R. D. Connor and A. D. C. Simpson, Weights and Measures in Scotland: A European Perspective, ed. by A. D. Morrison-Low (NMSE, 2004), p. 752.

[3] Connor & Simpson, Weights and Measures in Scotland p. 752.

[4] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 65.

[5] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 32.

[6] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 22.

[7] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 70

[8] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 21.

[9] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 66

[10] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 34.

[11] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures p. 23

[12] Buchanan, Tables for Converting the Weights and Measures pp. 78-79

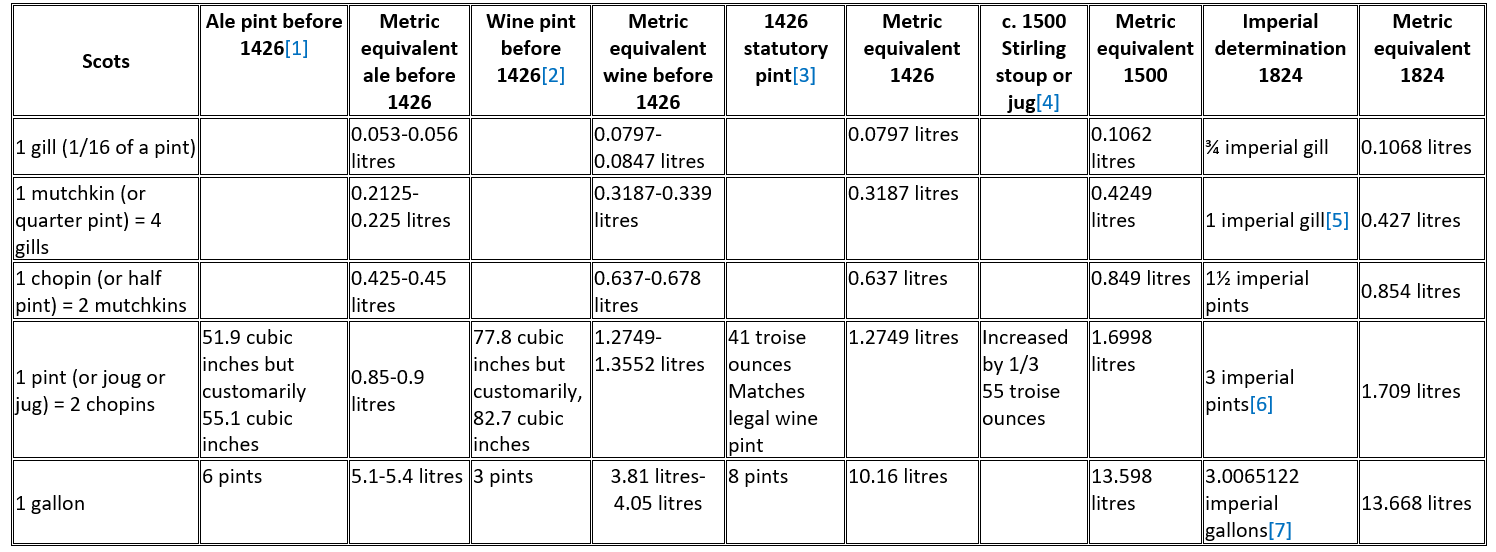

The main unit of liquid capacity was the Scots pint (originally from the Latin, pingo, pinctum meaning ‘to paint’, via various European languages, such as the French pinte and Dutch pint; equating the size of the measure with a painted mark on a measuring jug or bowl). The pint was sometimes referred to as the ‘jug’ or ‘joug’. Before 1426 there were 6 pints in a gallon (from the old French galon or jalon, meaning a ‘jar’ or ‘bowl’) and after 1426 this was changed to 8 pints in a gallon. Half a pint was a chopin (from the French liquid measure, the chopine), and a quarter of a pint was a mutchkin (from the diminutive of a kind of cap, a mutch). A sixteenth of a pint was a gill (from the Old French, gelle, a wine measure or ‘flask’). The size of a pint, from which all other measures are derived, was increased in 1426 and again in c.1500.[8] Before 1426 there were separate measures for ale and wine. Note that metric equivalents shown should be regarded as approximate.

The main unit of liquid capacity was the Scots pint (originally from the Latin, pingo, pinctum meaning ‘to paint’, via various European languages, such as the French pinte and Dutch pint; equating the size of the measure with a painted mark on a measuring jug or bowl). The pint was sometimes referred to as the ‘jug’ or ‘joug’. Before 1426 there were 6 pints in a gallon (from the old French galon or jalon, meaning a ‘jar’ or ‘bowl’) and after 1426 this was changed to 8 pints in a gallon. Half a pint was a chopin (from the French liquid measure, the chopine), and a quarter of a pint was a mutchkin (from the diminutive of a kind of cap, a mutch). A sixteenth of a pint was a gill (from the Old French, gelle, a wine measure or ‘flask’). The size of a pint, from which all other measures are derived, was increased in 1426 and again in c.1500.[8] Before 1426 there were separate measures for ale and wine. Note that metric equivalents shown should be regarded as approximate.