Cockburn Association

The Cockburn Association was founded in 1875 to promote and encourage the care and conservation of Edinburgh’s unique architectural and landscape heritage.

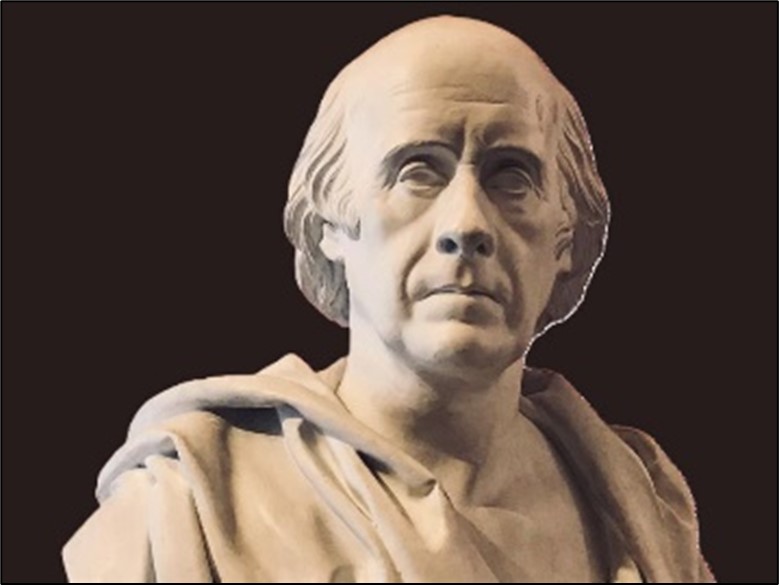

The Association is one of the oldest conservation, planning and architectural advocacy organisations in the world. It takes its name from Lord Cockburn (1779-1854), a renown Scottish lawyer, judge and literary figure, who can claim to be one of Scotland’s first conservationists. His 1849 publication A Letter to the Lord Provost on the Best Ways of Spoiling the Beauty of Edinburgh provided the inspiration to establish a popular organisation and it remains as relevant today as when it was first penned.

The Cockburn Association’s objectives are to promote and encourage:

- the maintenance, improvement and promotion of the amenity of the City of Edinburgh and its neighbourhood;

- the protection, preservation and conservation of the City’s landscape and historic and architectural heritage.

From the outset, the Association’s ambitions have been forward-looking. At its inaugural meeting in 1875, it expressed its initial objectives as creating publicly accessible green spaces for recreation; reducing air and water pollution; regulating and improving building standards and preserving the best of the city’s existing architecture treasures.

Today, its concerns range from conservation of the city’s architectural heritage, to the liberalization of planning and other regulatory systems guiding good development, and to the commodification of civic spaces and overtourism.

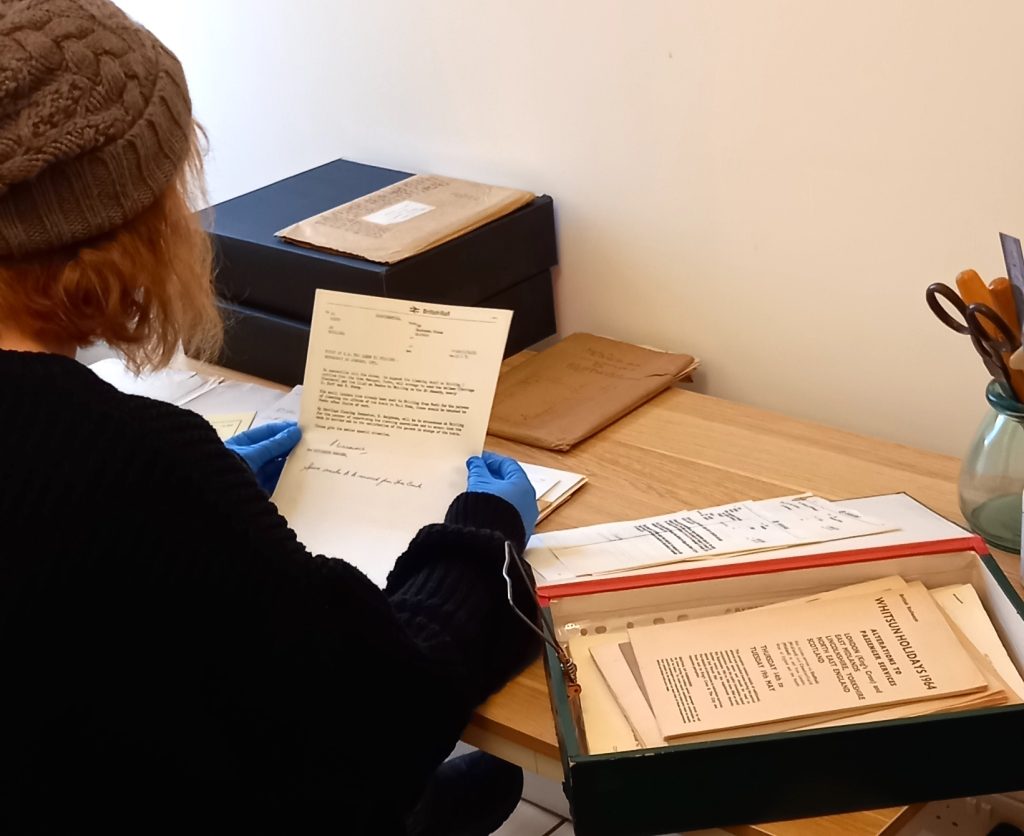

Archive Access and Management

The Cockburn Association’s Archive Collections provide a rich resource on heritage, amenity and development issues and history. They include:

- The official Archive records of the Association including records of its governing Council and Committees, correspondence, Annual Reports, newsletters and other publications.

- A valuable collection of photographs, plans, submissions and other documents relating to specific policy and development casework, ranging from architectural proposals to major public policy initiatives and issues in which the Association has been involved over the years.

- Substantial Boxes including collection of pamphlets, reports, publications and other materials relating to planning in Edinburgh.

Cataloguing and partial digitisation of the archives collections is currently in progress. This forms part of the 150th anniversary activities over the course of 2025-26, with the intention of publishing on-line core material such as Annual Reports, Newsletters and Minutes of meetings.

Materials can be accessed by researchers by appointment at the Cockburn’s premises in Edinburgh. Digital or print copies may also be provided for relevant materials, subject to a fee and subject to any copyright or other restrictions.

The Cockburn Association

Trunk’s Close, 55 High Street

Edinburgh EH1 1SR

T: (44)131-557-8686

www.cockburnassociation.org.uk

archives@cockburnassociation.org.uk

- Minute Book containing business meetings, such as this one from 13 July 1896 attended by Chair, Scott Moncrieff and Professor Patrick Geddes

- Publication of University’s development plans from 1962

- Member’s Ticket to first Annual General Meeting 28 June 1876

- Royal High School – in 2017, the Association initiated a campaign against proposals to convert this iconic Greek revival historic building into a hotel. Public inquiry material is held in digital files

For more information, view Cockburn Association repository page